Tokyo, December 22, 2011, 8:00 am. We, along with the crew of German TV channel ZDF, loading our stuff and equipment into a van and drive out to the shooting in Fukushima prefecture (福岛県). Since March 2011, it is the most famous Japanese prefecture, just like our Chornobyl, which became notorious throughout the world since April 1986.

Tokyo, December 22, 2011, 8:00 am. We, along with the crew of German TV channel ZDF, loading our stuff and equipment into a van and drive out to the shooting in Fukushima prefecture (福岛県). Since March 2011, it is the most famous Japanese prefecture, just like our Chornobyl, which became notorious throughout the world since April 1986.

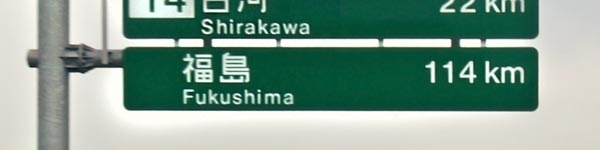

Outside the window of our Toyota HiAce strange, unusual, as for me, landscape. I, for many years, get used to the road in the “Zone”, our Chornobyl Exclusion Zone, where I know every turn, every town and village along the way. But here all is different: outside the window of the van are mountains, on road signs names of settlements are written with beautiful, but totally incomprehensible for me kanji patterns, cars drive on the other side of the road and even trees and shrubs, despite of the end of December, are green.

|

|

|

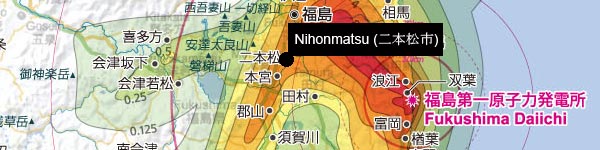

After the accident at the nuclear power plant Fukushima Daiichi (number 1), in March 2011, the Government evacuated the residents of the 20–kilometre zone around the accident and closed any free access to it, but the real disaster zone extends for a hundred kilometres beyond the “Fukushima Twenty”. Radioactively contaminated are most part of Fukushima Prefecture and some parts of adjoining prefectures of Miyagi, Ibaraki and Tochigi. In mid-April of that same year to a 20–km restricted zone were added another area of the recommended evacuation, which stretches for 50 kilometres in a north–westerly direction. But, despite the recommendations and requests of the Government, in radioactively contaminated towns and villages some people are still living. Someone dropped everything and left, someone sent children to relatives in clean areas, but overall, the region continues, or at least trying to live its usual life.

But there are areas not included in the north–west trail and formally requests and recommendations of the Government pass them by, although judging by the map of radioactive contamination, the situation there is not much better than in “Twenty” and the north–west “Fifties”. One of such places – the city of Nihonmatsu.

We are halfway to our destination, and I start to look more often at the wrist search dosimeter-radiometer. Gamma background gradually begins to rise: 0.25 –> 0.3 –> 0.5 µSv/h. I turn on the spectrometer mode – it's pretty expected: 134Cs, 137Cs. My acquaintance with “Fukushima spectrum” took place.

We are making a brief stop near a roadside café–shop. I take this opportunity to run with my devices on the roadside. If on the road, and the more, inside the bus was 0.5 µSv/h, on the roadside in the grass will be at least twice more (it’s the rigorous Chornobyl rule). And I got complete disappointment and shock of the foundations – roadside is clean: 0.15 µSv/h. While our group drinks coffee in front of our van, I’m in confusion wander with dosimeters along the road. It cannot be, it is not correct. It turns out that it’s only the road is “dirty” – the radioactive dirt was extended for hundreds of kilometres with the car wheels.

Nihonmatsu (二本松市)

A few words about the city: Nihonmatsu located in Fukushima prefecture, Tōhoku region, on the island of Honshū. The population is about 60 thousand people. From Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant to Nihonmatsu about 60 km by airline.

In the vicinity of Nihonmatsu we should meet with a local farmer Mr Masami Yoshizawa who is waging uphill battle for his herd of 300 cows left in the 20 km evacuation zone, near the town of Namie (浪江町). The government encouraged farmers to euthanize their animals. Masami Yoshizawa (吉沢正己) and Atsushi Murata (村田淳) have ignored this recommendation and already more than nine months regularly go into the forbidden zone to feed their cows.

On the way we make a stop at Motomiya (本宫市), a city bordering the Nihonmatsu.

|

|

|

In the local minimarket we buy a couple boxes of sushi and arrange lunch right in the car park near the store. A feeling of unreality did not leave me. In my memory pops up: “Do not eat, drink, smoke at ten–kilometre zone of Chornobyl nuclear power plant”. But we are not at the Chornobyl NPP zone and it is about 60 km to Fukushima Daiichi. But is it more clear here? Cars ride through the streets, the locals are routinely carry out purchase from the store, the students go home from school, but on my dosimeter is about 0.6 µSv/h. As I mentioned above, in spite of the contamination, the area did not get into the so-called voluntary evacuation zone.

After lunch we go to the stock farm of Masami Yoshizawa. On the road we make a stop at the rice fields. Gamma background level is 1–1.5 µSv/h.

Kenzo Hashimoto (橋本健三), American journalist, as well as our translator and the contactor, look questioning on my manipulations with devices.– How many it shows? Is that a lot?

– It depends for what. It is not too much for a short visit, but definitely one shouldn't live and farm here.

Hashimoto is upset:

– But how do they live? Rice is the main crop of the region! If there is so much in soil, so how many will be in the rice?

– It is necessary to measure rice. Take it to the lab and measure. I can only say that this area is radioactively contaminated. Gamma background here exceed natural one at least five times. It is impossible to grow an environmentally safe rise here. Either remove the entire top layer of soil and take it to burial ground for radioactive waste or wait for about 100 years until the 137Cs does not decay to a safe minimum.

We never met Masami Yoshizawa. We wander about the stock farm and talked with several of its employees. From them we learned some details about the farmer Yoshizawa’s fight for his herd of cattle, which segued into a struggle for all left domestic animals in the area. As the government promises a rather symbolic compensation to farmers for their cows, so farmers, which it is quite obvious, if do not expect a complete bankruptcy, then at least the huge financial losses. Some farmers do not give up and try to “grasp at any straw”. As a “straw” Masami Yoshizawa chose the idea of creating in the evacuation zone some experimental research laboratory–farm. I immediately remembered our research farm in the Chornobyl area at Novoshepelychi. But there have kept only some dozen heads, and here in the 20 km zone at the moment there are about 1,000 head of livestock and it is difficult for me to imagine such a large research farm. And all that could be research in this area, have researched long ago.

|

|

|

On the stock farm gamma background is about 0.8–1 µSv/h, sometimes up to 2.5 µSv/h. And no, it's not “That Particular Stock Farm in the Zone”, where the farmer Yoshizawa and activists of environmental organizations, despite of the strict prohibitions of the authorities, wriggle to feed the running wild livestock. By local standards it is quite safe and almost not radioactively contaminated.

Our contactors Kenzo Hashimoto and Makoto Hori by turns call on the phone trying to contact Masami Yoshizawa. After all we did not understand what happened to Yoshizawa, whether he was unable to meet us, or did not want to. Time towards evening and filming is over for today. Alex and Steffi loaded camera and microphone in our minibus. That’s all for today. We drive to the west of the prefecture to the Hatoriko Highland Regina Forest Resort, where tomorrow, December, 23 will be a meeting of children evacuated from the 20–kilometre zone around the accident Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant.

Many thanks for organizing the trip, support and assistance to Alexander Detig, Tatyana Ivanova Detig, Stefanie Jaehde (company Sound & Vision); second channel of German television ZDF, Mr Kanji Takahara 高原 寛司 (TV TOKYO Corporation), Mr Naoki Ban 伴直樹 (Gazeta USA). Special thanks to our accompanying Mr Kenzo Hashimoto 桥本 健三 (Gazeta USA) and Mr Makoto Hori 堀 信 (Tokyo Sound Production).

| Classmates. Fukushima Prefecture. The Second Day< Prev | Next >ChNPP. Installation of the new ventilation stack of the second stage |

|---|